Disclaimer:

The content on this blog reflects personal views and insights aimed at enhancing mental health awareness. It is for informational purposes only and should not be considered academic material or a substitute for professional psychological advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Mental health is complex, and individual needs vary—always seek guidance from a qualified mental health professional for personalized support. If you are in crisis or require immediate assistance, please reach out to a licensed mental health provider or emergency services.

This piece explores themes of trauma and its lived experiences. If you find such topics triggering, please proceed with caution or seek support as needed.

About the Author and Article –

As a clinical psychologist and researcher with experience in trauma and mental health. My work has focused on understanding the ways trauma shapes the body, mind, and relationships, and I draw from both clinical insights and literary metaphors to make these experiences relatable. Kafka’s Metamorphosis and Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score have profoundly informed my understanding of trauma, which I aim to share here.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

I’ve often wondered what it feels like to wake up and no longer recognize yourself—not in the poetic sense of growth or change, but in the terrifying way that leaves you estranged from your own body, your own mind. Kafka’s Metamorphosis captures that feeling in a way that is both visceral and haunting.

| S.No. | Content |

| 1 | Prisoner of the Body |

| 2 | The Silence of the Unspoken |

| 3 | The Weight of Shame |

| 4 | Fractured Bonds |

| 5 | Denial and the Struggle for Control |

| 6 | A mirror to Trauma’s Realities |

1. Prisoner of the body:

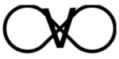

Gregor Samsa’s transformation into a grotesque insect felt, to me, less like a work of fiction and more like a metaphor brought to life—a metaphor for trauma. Kafka doesn’t just show us what happens to Gregor; he makes us feel it. Trauma, after all, isn’t just something you experience and leave behind. It lingers. It changes you. It settles into your body in ways you can’t always name. As Bessel van der Kolk puts it in The Body Keeps the Score, “The past is alive in the form of gnawing interior discomfort.”

Kafka describes Gregor’s grotesque form with painstaking detail—the spindly legs, the rigid carapace, the inability to lie comfortably. It’s not just physical discomfort; it’s a loss of autonomy and familiarity. Gregor avoids even looking at himself, closing his eyes against the unbearable truth of his new reality. This visceral rejection reminded me of how trauma survivors often speak of feeling estranged from their own bodies, disconnected from the physical self they once knew.

2. The Silence of the Unspoken

But it wasn’t just Gregor’s physical transformation that stayed with me—it was his silence. Or, more precisely, his inability to communicate.

His voice, once a bridge to others, becomes distorted, unintelligible. Kafka describes it perfectly:

“Deep inside him was a painful and uncomfortable squeaking mixed in with it. The words could be made out at first, but then there was a sort of echo which made them unclear.”

This silence isn’t just about words. It’s about the profound isolation of feeling unheard. This is one of the cruelest aspects of trauma—it often renders people voiceless, unable to articulate their pain in ways others can understand. John Bowlby once said, “What cannot be spoken to the mother cannot be told to the self.” That line lingers with me, just as Gregor’s failed attempts to connect with his family do. For trauma survivors, this dynamic is all too familiar—the sense of screaming into a void where no one truly listens.

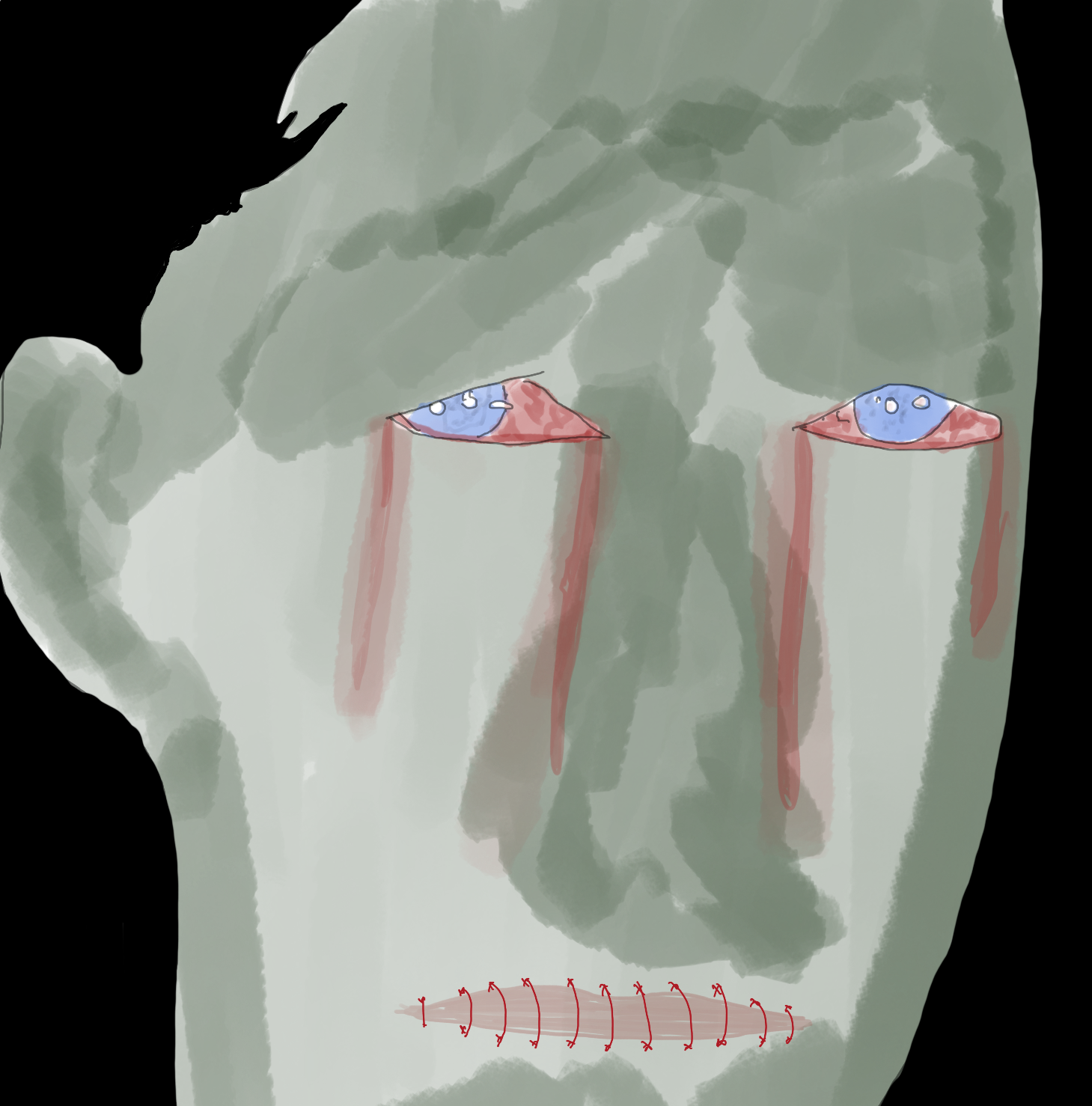

3. The Weight of Shame

Shame is one of trauma’s most insidious companions. It burrows deep, convincing survivors that their suffering is a reflection of their worthlessness. From the moment Gregor awakens in his new form, shame becomes his shadow. He hides himself, recoiling from the sight of his own body, and when he ventures out, it’s with an overwhelming fear of disgust and rejection. Kafka writes, “He was no longer the same, and he felt a great sense of shame.” It’s a powerful distillation of how trauma can strip away one’s sense of dignity, leaving only the ache of self-reproach.

Shame is more than a feeling; it’s a physical and emotional burden that reshapes how individuals perceive themselves and the world around them. In The Body Keeps the Score, van der Kolk explains, “Trauma victims cannot recover until they become familiar with and befriend the sensations in their bodies.” Shame complicates this process, making the body itself a source of discomfort and alienation. For Gregor, every movement in his grotesque new body amplifies this alienation, making him feel unworthy of care or connection.

This shame isolates. It silences. It convinces survivors to hide not only from others but from themselves, avoiding the pain of confronting their transformed realities. Kafka’s portrayal of Gregor captures this with unflinching clarity, reflecting the profound internal struggle of anyone navigating the complexities of trauma.

4. Fractured Bonds:

In Metamorphosis, Gregor’s transformation doesn’t just alter his body; it destabilizes the connections he once relied on. The warmth and familiarity of his relationships dissolve under the weight of his new reality. Though his family initially attempts to help, their discomfort and inability to cope create a distance that grows insurmountable. For Gregor, the trauma of his condition is compounded by the loss of intimacy and trust, leaving him isolated within his own home. His sister begins as a caregiver, but her compassion wanes, replaced by frustration and resentment. His father grows cruel and domineering. His mother retreats into denial.

Trauma rarely confines itself to the individual—it reverberates outward, reshaping relationships in ways that are often subtle but deeply felt. It changes how survivors relate to others, how they express their needs, and how they interpret the intentions of those around them. As van der Kolk writes in The Body Keeps the Score, “Unresolved trauma can take a toll on relationships. It often triggers survival defenses that are inappropriate for the present but were crucial in the past.”

This is one of trauma’s cruelties—it fractures the very bonds that survivors most need for healing. Relationships can become strained as loved ones struggle to understand the survivor’s experience, often misinterpreting their behaviors or withdrawing out of their own discomfort. The ripple effects of trauma, as Kafka so poignantly illustrates, extend far beyond the individual, creating barriers where connection once thrived.

5. Denial and the Struggle for Control

One of the most poignant aspects of Metamorphosis is the theme of denial. Even as Gregor’s body changes beyond recognition, he clings to the hope of returning to work, of resuming his old life. It’s heartbreaking to watch because we, as readers, know the truth—there’s no going back. Trauma often does that. It creates a chasm between the past and the present, one that can’t simply be crossed with willpower or determination. To quote Bessel van der kolk from Body keeps the score “ Nobody can ‘treat’ a war, or abuse, rape, molestation, or any other horrendous event, for that matter; what has happened cannot be undone. But what can be dealt with are the imprints of trauma on body, mind and soul”

And yet, denial is a natural response. It’s a way of coping, of avoiding the unbearable. Kafka shows this not only in Gregor but in his family, who pretend, for as long as they can, that his transformation isn’t as catastrophic as it clearly is. But avoidance, as we know, is no solution. It offers temporary relief but ultimately prevents healing.

6. A Mirror to Trauma’s Realities

Kafka’s Metamorphosis is more than a surreal tale—it’s an unflinching exploration of the many dimensions of trauma. Gregor’s transformation is not just physical; it’s relational, emotional, and deeply symbolic. It captures the alienation, the silence, the shame, and the yearning for a life that no longer exists.

Reading Gregor’s story, I was reminded of van der Kolk’s assertion that “trauma survivors need to find their way to a safe space where they can reconnect with themselves and with others.” Gregor never finds that space, and that’s what makes his story so devastating. But it’s also what makes it so important. It forces us to confront the reality of trauma—not as a distant concept but as a lived experience, one that demands empathy and understanding.

And yet, through all this darkness, there’s something quietly profound in Gregor’s story. Even in his suffering, there’s a resilience. He learns to navigate his new body, to adapt, even as the world around him crumbles. It’s a muted kind of hope, a reminder that survival itself is an act of defiance.

Kafka doesn’t just show us Gregor’s suffering—he invites us to feel it. And in doing so, he challenges us to confront the complexities of trauma with greater empathy. For me, Metamorphosis is not just a story; it’s a lens through which we can better understand the human condition, a call to see the unseen and to hear the unheard, to create the kind of connections that can transform pain into healing.

And maybe, just maybe, it’s a reminder that even in our darkest metamorphoses, there’s a flicker of light waiting to be found.